Not all waiting is the same, of course. There is "waiting when you know," like the way we wait for a wedding day after a long engagement. There is "waiting when you don't know," like the waiting after an MRI or a biopsy. In one case, the waiting condenses time, turning months into weeks or days; in the other, time is expanded, and every day is a lifetime.

There is also "waiting when you know some but not all," like the way a mother waits the birth of a child. That, I think, is sometimes the kind of waiting that keeps you awake at night, with minutes stretching into hours; and at other times, turning months of changes and expectation into a cascade of time inadequate to the preparation needed for the sea change that the arrival of the tiny stranger will herald.

Advent is a specific kind of waiting. It's waiting for the good news that we've heard throughout our lives to come true, when our desire is finally met by a gift that shows us, all at once, that our happiness depends on the happiness of every other person, a happiness we need to make possible. It's waiting for the moment when, in every person simultaneously, the good work that God began in us, the possibility that we know is within us, is realized.

My problem, our problem, with waiting is not just that I am cog in a culture that, in its never-ending quest for efficiency, has put delaying gratification at the bottom of its to-do list by making it obsolete. If we keep our desires modest, within our means, appropriate to us, we can pretty much have whatever we want by driving a few minutes or touching the "buy now" button on a phone app. Delaying gratification is so 20th century. I can pretty much get whatever I want. Waiting is overrated! The trouble is that I keep being told what I need to have, and when I get what I want, the Next Great Thing is beckoning, and I'm not complete without it. I ought to be able to stop, be a rational human being, be Myself, and Just Say No.

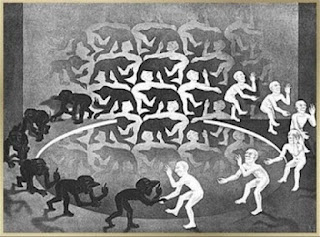

The trouble is, desire doesn't work that way. "We desire according to the desire of the other," for one thing. The entire advertising industry, with an annual budget of well over half a trillion dollars (think about that—half a trillion dollars not to purchase something, but to make us want to purchase something), exists for one purpose only: to make us believe that we want things we don't have, and in many cases, don't even know exist. Some, in fact, don't exist, and we want them anyway, before they're even a reality. The way that advertising works isn't just telling us about a product; it suggests that we're not complete without a product, and that those who have the product have an advantage over us. They're smarter, prettier, more successful, have an easier life. Our mimetic desire kicks in, and unless we are very careful and discriminating, can take our imitative cues from Someone other than culture, we get caught in the spiral of wanting and possessing. Taking those imitative cues from the gospel, though, requires that we slow down, take inventory, and wait. When are we going to do that?

And not everyone has the means to even achieve modest desires. In fact, probably most people don't, when we consider the human race as a whole. And we still desire according to the desire of the other, which means there's a world of rivalry and perhaps violence waiting just a few milliseconds into a future which started, well, yesterday. Certainly the prosperity gap between factory workers in China and India, southeast Asia and Central America and consumers in western Europe, Japan, and the United States points this up, though the fault lines of violence show themselves in the disenchantment and radicalization that materializes in subcultures of gangs, organized crime, and of course, ethnic and religious violence. Unfocused rage and the vigilante avenging of systemic injustice arise everywhere. In the absence of genuinely good news, people grasp for and claim their own bounty, however bloodily acquired. Waiting is overrated. We take what we think we need. We take what we desire.

The days are coming, the gospel says, when an apocalyptic Son of Man, a "human being," will begin to clean up the upside-down world of our invention that replaced equality with entitlement and divine bounty with scarcity economics. "God Our Justice" is coming with "safety and security," which, along with "health," is what "salvation" means. Apocalyptic visions, nearly always born out of a matrix of violence, tend to predict violent divine solutions, because waiting is overrated. We can fix things fast by blaming and then neutralizing those who oppose our desires. But when "God Our Justice" actually shows up, it's generally in the guise of reconciliation commissions rather than forced apartheid, solidarity marches and nonviolent civil disobedience rather than riots and lynchings, and field hospitals of Medicins sans Frontières rather than in laser-guided bombs and SEAL teams. Advent waiting, waiting for good news, is waiting for something we heard on occupied streets, or whispered in darkness of a gulag, or remembered from a Sunday school class about the jubilee, to finally come true.

There is also "waiting when you know some but not all," like the way a mother waits the birth of a child. That, I think, is sometimes the kind of waiting that keeps you awake at night, with minutes stretching into hours; and at other times, turning months of changes and expectation into a cascade of time inadequate to the preparation needed for the sea change that the arrival of the tiny stranger will herald.

Advent is a specific kind of waiting. It's waiting for the good news that we've heard throughout our lives to come true, when our desire is finally met by a gift that shows us, all at once, that our happiness depends on the happiness of every other person, a happiness we need to make possible. It's waiting for the moment when, in every person simultaneously, the good work that God began in us, the possibility that we know is within us, is realized.

My problem, our problem, with waiting is not just that I am cog in a culture that, in its never-ending quest for efficiency, has put delaying gratification at the bottom of its to-do list by making it obsolete. If we keep our desires modest, within our means, appropriate to us, we can pretty much have whatever we want by driving a few minutes or touching the "buy now" button on a phone app. Delaying gratification is so 20th century. I can pretty much get whatever I want. Waiting is overrated! The trouble is that I keep being told what I need to have, and when I get what I want, the Next Great Thing is beckoning, and I'm not complete without it. I ought to be able to stop, be a rational human being, be Myself, and Just Say No.

The trouble is, desire doesn't work that way. "We desire according to the desire of the other," for one thing. The entire advertising industry, with an annual budget of well over half a trillion dollars (think about that—half a trillion dollars not to purchase something, but to make us want to purchase something), exists for one purpose only: to make us believe that we want things we don't have, and in many cases, don't even know exist. Some, in fact, don't exist, and we want them anyway, before they're even a reality. The way that advertising works isn't just telling us about a product; it suggests that we're not complete without a product, and that those who have the product have an advantage over us. They're smarter, prettier, more successful, have an easier life. Our mimetic desire kicks in, and unless we are very careful and discriminating, can take our imitative cues from Someone other than culture, we get caught in the spiral of wanting and possessing. Taking those imitative cues from the gospel, though, requires that we slow down, take inventory, and wait. When are we going to do that?

And not everyone has the means to even achieve modest desires. In fact, probably most people don't, when we consider the human race as a whole. And we still desire according to the desire of the other, which means there's a world of rivalry and perhaps violence waiting just a few milliseconds into a future which started, well, yesterday. Certainly the prosperity gap between factory workers in China and India, southeast Asia and Central America and consumers in western Europe, Japan, and the United States points this up, though the fault lines of violence show themselves in the disenchantment and radicalization that materializes in subcultures of gangs, organized crime, and of course, ethnic and religious violence. Unfocused rage and the vigilante avenging of systemic injustice arise everywhere. In the absence of genuinely good news, people grasp for and claim their own bounty, however bloodily acquired. Waiting is overrated. We take what we think we need. We take what we desire.

The days are coming, the gospel says, when an apocalyptic Son of Man, a "human being," will begin to clean up the upside-down world of our invention that replaced equality with entitlement and divine bounty with scarcity economics. "God Our Justice" is coming with "safety and security," which, along with "health," is what "salvation" means. Apocalyptic visions, nearly always born out of a matrix of violence, tend to predict violent divine solutions, because waiting is overrated. We can fix things fast by blaming and then neutralizing those who oppose our desires. But when "God Our Justice" actually shows up, it's generally in the guise of reconciliation commissions rather than forced apartheid, solidarity marches and nonviolent civil disobedience rather than riots and lynchings, and field hospitals of Medicins sans Frontières rather than in laser-guided bombs and SEAL teams. Advent waiting, waiting for good news, is waiting for something we heard on occupied streets, or whispered in darkness of a gulag, or remembered from a Sunday school class about the jubilee, to finally come true.

The "Son of Man" is Emmanuel, is the God-with-us promised long ago. God is already present with us, fully, incarnationally, committed to the world, waiting for us to accept the invitation made in Christ to be a part of the great peaceful clean-up that begins with a change of direction and vision for us. It's a change of desire that we need. Advent is God waiting, too. God waits for us to believe that the coming-near of God is on our behalf, life-giving beyond our wildest expectations, and without any of the projected malice or envy or violence with which we have re-created gods in our own image. Once we stop receiving our selves from the violent, desire-driven culture and begin receiving it from the loving, free-for-all God whose desire is the very best for each and everyone at once, whose desire not to acquire but to give away in freedom the life and love that are God's very being, we can begin to act in a new way for others, in a truly catholic way, rejecting any definition of a self that is against another, but including every being in the gentle messianic kingdom.

So we wait for God-with-us in the chaos that ensues when death, sickness, or failure disconnects the most fundamental of our relationships of love, family, and friendship, and we or our loved ones are at sea in grief and loss.

We wait for God-with-us in our regret of the destruction we've wrought by our choices, in the fear we feel for being discovered as impostors in our own story, in both the laziness and the self-interest that leads us to support by our politics the very structures against which we dare to pray every Sunday.

We wait for God-with-us in the terror of violent streets, the horror of ethnic and religious purges and persecution, the scapegoating of minorities, refugees, immigrants, the rhetoric of exceptionalism and a gospel of prosperity.

During Advent, we sing and say, "We will wait for you," to the one who is closer-by than our own consciousness, nearer to us than the atmosphere. "God our justice, we will wait for you all day long." And the one who draws near with depthless benevolence replies, "And I for you, my peace, my justice, my people. I will wait for you."

What we sang today:

Entrance: The King Shall Come When Morning Dawns

Penitential litany based on "O Come, O Come, Emmanuel"

Psalm 25 "To You I Lift My Soul" (Haugen)

Advent Gospel Acclamation (Joncas)

Presentation of Gifts: Come to Us, O Emmanuel (Haugen)

Mass of St. Aidan

Communion: Walk in the Reign

Recessional: Canticle of the Turning

So we wait for God-with-us in the chaos that ensues when death, sickness, or failure disconnects the most fundamental of our relationships of love, family, and friendship, and we or our loved ones are at sea in grief and loss.

We wait for God-with-us in our regret of the destruction we've wrought by our choices, in the fear we feel for being discovered as impostors in our own story, in both the laziness and the self-interest that leads us to support by our politics the very structures against which we dare to pray every Sunday.

We wait for God-with-us in the terror of violent streets, the horror of ethnic and religious purges and persecution, the scapegoating of minorities, refugees, immigrants, the rhetoric of exceptionalism and a gospel of prosperity.

During Advent, we sing and say, "We will wait for you," to the one who is closer-by than our own consciousness, nearer to us than the atmosphere. "God our justice, we will wait for you all day long." And the one who draws near with depthless benevolence replies, "And I for you, my peace, my justice, my people. I will wait for you."

What we sang today:

Entrance: The King Shall Come When Morning Dawns

Penitential litany based on "O Come, O Come, Emmanuel"

Psalm 25 "To You I Lift My Soul" (Haugen)

Advent Gospel Acclamation (Joncas)

Presentation of Gifts: Come to Us, O Emmanuel (Haugen)

Mass of St. Aidan

Communion: Walk in the Reign

Recessional: Canticle of the Turning