There's a fire in the city,

There is blood that cries to the sky.

There's a fire in the city,

There is blood that cries to the sky.

I've written about inspiration before, as in, "What inspires you to write a song?" One answer, and for me it truly is down the list, is "a commission." Nothing gets you down to work quite like the need to pay the rent, but with that comes a certain amount of pressure and anxiety, and so I prefer to allow natural forces like that "inner light" and communal need to be the source of my inspiration most of the time.

But another source of inspiration is the rare occasion when a large catechetical conference, or another regional or national gathering of church folk, asks you to write the theme song for said conference. This is particularly inspiring because it's an indication that someone(s) values the "style" of your contribution to the repertoire of church music, and it further means there will be an immediate and receptive performing audience for the work, one that can help launch a work onto a wider local or even national scene in a way that no concert or group of concerts or catalog can.

This has happened to me more than once, but not quite a handful. "I Am for You" was written for a small conference in Hawaii, "Trumpet in the Morning" was for a millennium-preparing 1998 East Coast RE conference. "Turn Around," alternatively called "Announce the Good News," is from my unreleased collection and was part of JustFaith's national release of a small-community based training program on Catholic social teaching. But there's really no equal to the opportunity afforded by being asked to write the theme song for the Los Angeles Religious Education Congress (LAREC) held annually at the Anaheim convention center and jointly sponsored by the archdiocese of Los Angeles and the diocese of Anaheim, and attended by 20,000-30,000 people, with liturgies and other prayer services held in the convention center arena, home of hockey's Mighty Ducks. I've been blessed twice with that invitation, the second time co-writing the theme song with Gary Daigle, "Way, Truth, and Life." The first time was for the 1994 conference, and the song became "Live the Promise."

"Live the Promise?" I can hear you asking. What the heck is that?

I forgot to mention that this kind of a launch is no guarantee of a hit, no matter how highly the songwriter may think of the work. It just doesn't work like that. Sometimes a song translates into the kind of thing that makes its way into the repertoire, sometimes it doesn't. But the song still has a story, and even after all this time, I keep believing in it, like a late-blooming child.

LAREC is held each year in the late winter/early spring, usually around the first or second Sunday in Lent. 1994 was a "B" lectionary year like this year, and the conference was held in the days preceding and ending on the first Sunday in Lent. Part of writing for a conference is taking their theme text and notes and shaping that into a song for the event. But there is a sense (for me at least) that the song has to have legs, has to be able to be used beyond that single event, wonderful as it is, and at liturgies in normal churches on normal Sundays sung by normal choirs and congregations. Congress events are definitely special-needs events. The size of the arena, the festivity of the days, the ethnic mix of the participants, all of these things shape the way the songs are written. So with the conference ending on the first Sunday of Lent in a B year, I wanted to nod to the scriptures of that weekend, because that, at least, would give the song the possibility of some staying power. "Live the Promise/Viva la Promesa" was the theme of Congress, so that was my title. Where to go from there?

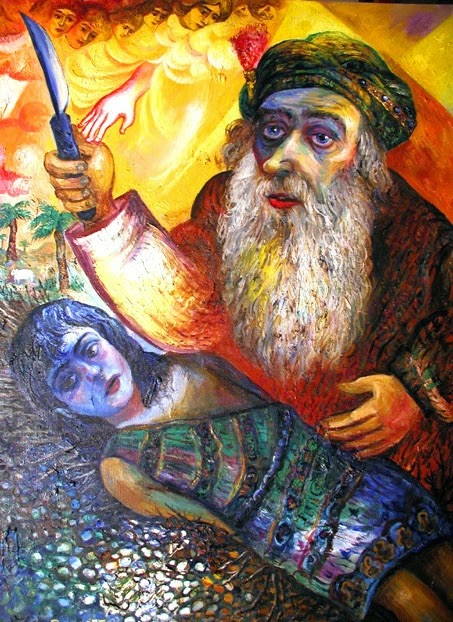

Hope in the midst of chaos was the heart of the theme, with the aftermath of the race riots following the Rodney King verdict still smoldering (literally) in the city and outlying area. For myself, I heard in the Genesis story of the flood and rainbow, paired with the gospel about the temptation of Jesus in the desert after his baptism, the promise of a different world, one where even God hangs the divine warrior's bow in the sky as if to say, "No more violence from me. That's not my style." It's a world where Jesus refuses the warhorse of the expected messiah, and instead opts for Abba, the God of the bow-cast-aside, embracing humanity and all its limitations to announce that earth is the place where God's dream must come true.

What I did, then, was start with the promise suggested by the rainbow, the warrior's bow set in the sky, and went forward from there with images of sky and light and earth to describe the dream of God kept alive in the chosen throughout the history of our planet right up into our current day. Verses begin with the flood, then in turn go to the Exodus and pillar of fire, the nativity's star of Bethlehem, the crucifixion when Jesus was "stretched out on the sky," suggesting the rainbow again, and then moving right to the present day with the last two verses, "Fire in the city" and blood crying to the sky, and the "battle in the (human) family" and the "hole of death" in the sky, the environmental mess we have made of the planet. But through all that the repeated section of the verses urges us, "Hold on, hold on! Hold on to the promise and live!"

Because the conference is a conference of all kinds of Christians and not just musicians, I opted for a musical form (and lyric) with a lot of repetition and a familiar folk-gospel melodic form. My hope was that people wouldn't really need to see the musical notes for the song, or even the words so much, but that once they heard the

pattern of the words and music, they'd be able to join in on the song enthusiastically and physically, paying more attention to each other and any, say, processional activity than to a book. And freeing their hands for clapping. On two and four, of course.

Well, I don't know. I still pull this out at least once every three years to add to the mix on the first Sunday in Lent in year B, but I suspect there aren't a lot of others. Looking back at onelicense.net reports from the last B year, it appears, but let's just say it wouldn't amount to much lunch money for the week! The way I see it, "Live the Promise" has all the elements to make it useful, but there are downsides, too, like the length of the form and therefore the overall length of the song's development. It's the kind of song that doesn't really require a great choir or band to pull off; the choral parts suggested by the harmonic structure would just as easily be improvised even by moderately talented amateurs. Another element in the structure of the song as it's published is that each group of two verses and a chorus does a key jump of one whole tone, so the song begins in Eb, but goes through F and ends in G. Maybe this is off-putting, too, I don't know.

Was it Mae West who said, "If you have to explain the kiss, it's not much of a kiss"? I've spent a lot of electrons with this

apologia pro cantu sua and I think it's time to move on! If you're at St. Anne on Sunday, we'll be singing it, and probably saying goodbye to it until (at least) 2018. It was great fun to sing this to open our concert in St. Louis last month with Peter Hesed's wonderful choir from St. Margaret of Scotland. I got the feeling that the "performing audience" we were with felt the same way. One of these days, who knows, I might get this songwriting thing right.

Live the Promise

Music and lyrics by Rory Cooney

1. O God, you were a warrior, but you set your bow in the sky. (3x)

Hold on, hold on, hold on to the promise and live.

2. (We were) wandering in the desert when your cloud appeared in the sky. (3x)

Hold on, hold on, hold on to the promise and live.

Live, live the promise, live, live the promise. (2x)

We were wandering in the desert when your cloud appeared in the sky.

Hold on, hold on! Hold on to the promise and live.

3. (We were) searching for a savior when your star appeared in the sky. (3x)

Hold on, hold on, hold on to the promise and live.

4. Jesus was a healer, but we stretched him out on the sky. (3x)

Hold on, hold on, hold on to the promise and live.

Live, live the promise, live, live the promise. (2x)

Oh Jesus was a healer, but we stretched him out on the sky.

Hold on, hold on! Hold on to the promise and live.

5. Fire in the city! There is blood that cries to the sky. (3x)

Hold on, hold on, hold on to the promise and live.

6. (There's a) battle in the family, there's a hole of death in the sky. (3x)

Hold on, hold on, hold on to the promise and live.

Live, live the promise, live, live the promise. (2x)

There's a battle in the family, there's a hole of death in the sky.

Hold on, hold on! Hold on to the promise and live.

7. O God, you were a warrior, but you set your bow in the sky. (3x)

Hold on, hold on, hold on to the promise and live. (3x)

© 1994, GIA Publications, Inc., Chicago IL 60638. All rights reserved.

"Live the Promise" at the GIA website

As you probably are well aware, if you read this blog, the liturgy of Palm Sunday of the Lord's Passion, the Sunday before Easter, begins with a ritual blessing of palms, a reading of the appropriate year's version of the current synoptic gospel passage about Jesus's entry into Jerusalem that day, and then a solemn procession into the church to begin the liturgy of the word. There are some tradition antiphons for that procession, like "Pueri Hebraeorum" (The Children of the Hebrews), but of course as it often does the rubric provides for other appropriate songs as well.

As you probably are well aware, if you read this blog, the liturgy of Palm Sunday of the Lord's Passion, the Sunday before Easter, begins with a ritual blessing of palms, a reading of the appropriate year's version of the current synoptic gospel passage about Jesus's entry into Jerusalem that day, and then a solemn procession into the church to begin the liturgy of the word. There are some tradition antiphons for that procession, like "Pueri Hebraeorum" (The Children of the Hebrews), but of course as it often does the rubric provides for other appropriate songs as well.